The Soldier’s Leap

The end of 1688 saw much discontent with the Catholic monarchy, this was brought to a head when James’s wife gave birth to an heir, William of Orange was invited to intervene. When William landed in England James was compelled to flee the country. William was crowned in his place. But not everyone disapproved of the exhiled king. Those who supported him were known as Jacobites.

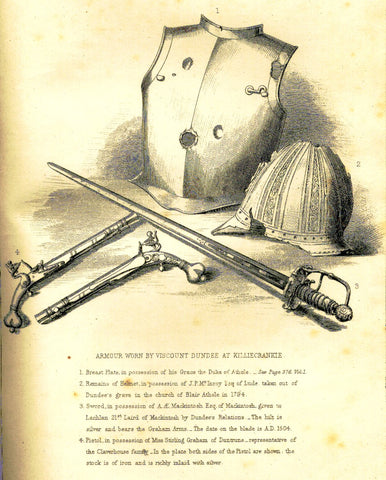

The Battle of Killecrankie

Support for King James was growing in the Highlands, John Graham of Claverhouse mustered support, among men still loyal to the ancient royal house of Scotland. The Macdonals of Keppoch were supporters along with the MacGregors and the Macdonalds of Sleat, Sir John Maclean of Duart and the Veteran Sir Ewen Cameron of Lochiel. The Jacobite forces marched towards Blair Castle, seat of the Atholls, a strategeic stronghold controlling several important routes. The Marquis of Atholl was away in England. During his absense Patricj Stewart of Ballachin seized the Castle and held it for the Jacobites.

The Estates had no choice but to confront Dundee, and sent against him an army under the command of General Hugh MacKay of Scourie, a veteran soldier from the Highlands, with 3,000 foot soldiers: his cavalry came by land. After weeks in fruitless pursuit of Dundee, Mackay also marched towards Blair Castle.

On the morning of 27th July Dundee determined to engage Mackay before he reached the castle, marched into Blair: at the same time Mackay’s army was making its way through the narrow defile of the Pass of Killiecrankie. The 4,000 government troops scrambled up the Pass on a narrow muddy pathway, where even three men found it difficult to walk abreast.

Watching their laborious progress from the Jacobite side was the renowned Atholl hunter, Iain Ban Beag Mac-rath, who shadowed them until they were within easy range. He had only one bullet and, shooting across the river, killed a calvalry officer near a gully which is still known as Troopers Den.

With only 2,500 men and few horses Dundee desperately needed the advantage of higher ground, then at about seven o’clock on the summer evening when the sun was no longer in the eyes of his troops, Dundee gave the order to charge. The fierce slaughter decided the outcome within two or three minutes. Two thousand men dead, wounded or captured – half Mackay’s army.

During the retreat, the only means of escape for one fleeing government soldier was a spectacular 18ft leap across the fast-flowing River Garry. The soldier, one Donald MacBean, recalled the event in a memoir published in 1728:

The sun going down caused the Highlandmen to advance on us like madmen, without shoe or stocking, covering themselves from our fire with their targes; at last they cast away their musquets, drew their broadswords, and advanced furiously upon us, and were in the middle of us before we could fire three shots apiece, broke us, and obliged us to retreat.

Some fled to the water, and some another way (we were the most part new men). I fled to the baggage, and took a horse in order to ride the water; there follows me a highlandman with sword and targe, in order to take the horse and kill myself. You’d laught to see how he and I scampered about. I kept always the horse betwixt him and me: at length he drew his pistol, and I fled; he fired after me.

I went above the Pass, where I met with another water very deep; it was about 18 foot over betwixt two rocks. I resolved to jump it, so I laid down my gun and hat and jumped, and lost one of my sloes in the jump. Many of our men were lost in that water.